Javelin Considerations: An online “makeup” clinic from Coach Gorski!

Note: Coach Jeff Gorski, our beloved lead coach of our Project Javelin Gold program, has been providing a javelin clinic at NBNO for many years. This year, due to medical reasons, he had to cancel at the last minute. Loving the javelin and the clinic the way he does, it's no surprise he sent us an "online clinic" to "make up" for not being able to come! So here's some great stuff for all throwers, especially you high school kids trying to get to the next level!

I consider myself a very lucky guy: I’ve had some success as an athlete and as a coach, which has allowed me to meet and talk with – or really to listen to – some of history’s greatest athletes and their coaches.

I consider myself a very lucky guy: I’ve had some success as an athlete and as a coach, which has allowed me to meet and talk with – or really to listen to – some of history’s greatest athletes and their coaches.

The variety of influences and information I’ve gleaned from them is part of a constantly evolving philosophy on throws training and technique. There are many ways to incorporate the fundamentals based on the ability and need of the athlete. Finding the best way for the basics to be effectively used is one of the challenges of coaching – which blend of positions, movements and concepts results in the longest throws and how do you produce them when needed?

Over the last 10-plus years I’ve had a great deal of discussions with some great javelin minds: Kari Ihalainen (Finnish national javelin coach), Kimmo Kinnunen (1991 World javelin champion & Finland’s U19 national coach) and Duncan Atwood (309 ft-plus in 1984, Olympic finalist). Each of these guys has been a wonderful source of information on every aspect of javelin throwing which has helped me grow as a coach and be more helpful to athletes I train regularly or work with at camps and clinics.

Javelin is very much a full body, reactive event that requires speed, power, flexibility and both physical and mental toughness. The margin for error is very small for big throws, but the window of things that can go wrong is pretty big, so a lot of time has to be spent ingraining the movements and concepts that lead to long throws and few injuries.

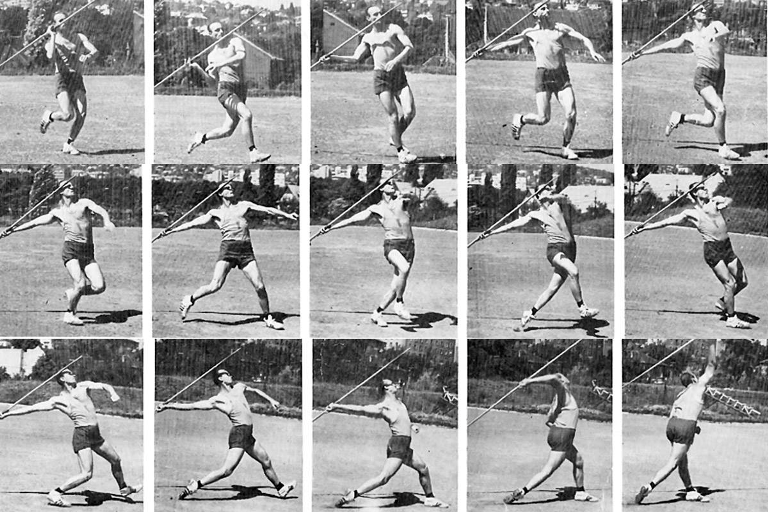

Just like building a house, this is a “ground up” progression: each body segment is dependent on the action of the previous one and will serve as the platform for the next segment to work from. This is both for power generation and technical positions – you can’t get a big release speed if you have poor leg timing or weak core ability. Understanding this is fundamental to a good training program and technical competence – big upper-body weight-room numbers will not add much distance if the leg effort in the run-up and plant do not give a platform for that upper body power to work from (Figure 1, at right).

As a coaching friend often says, “You can’t shoot a cannon from a canoe.” It’s very important to plan, train and understand that the legs give a huge percentage of the distance you throw and work to use them effectively. Explosive leg ability is needed for two reasons – to get the athlete down the runway in a relaxed and accelerating manner, and to suddenly stop that movement and be a stable base that the rest of  the throw comes from. In terms of training, the focus is more towards explosive, elastic power rather than raw strength; you’ll get better results by training for improved jumping ability than a heavy squat, for example. I can’t stress jumping ability enough; in all the throws, if jumping results improve and all else is the same, you will throw farther.

the throw comes from. In terms of training, the focus is more towards explosive, elastic power rather than raw strength; you’ll get better results by training for improved jumping ability than a heavy squat, for example. I can’t stress jumping ability enough; in all the throws, if jumping results improve and all else is the same, you will throw farther.

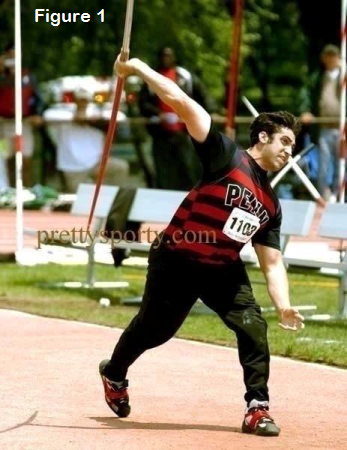

In technical terms, the leg action – once you get to the throwing position – is somewhat unique. While the right leg (for a right-hand thrower) is quite active, it is active in a clearing, pivoting action with a well-bent knee and not a driving or pushing action (Figure 2, at left). A bit of an explanation: The biggest factor in long throws is high release speed and the highest release speed is a result of an elastic reflex action of the muscles and connective tissue, not a willful muscular effort. And the fastest release will come from as many elastic reflex re-actions in proper sequence as possible, again, from the ground up.

So, as the thrower comes down the runway with acceleration, from each step you need to get to the plant or block at the fastest speed of the run-up and end that acceleration with a very firm and sudden jolt. That left leg impact is the main factor in producing the classic “reverse C” or “drawn bow” position (Figure 3, at right) that gets the whole body involved in the throw, not just shoulder and arm.

So, as the thrower comes down the runway with acceleration, from each step you need to get to the plant or block at the fastest speed of the run-up and end that acceleration with a very firm and sudden jolt. That left leg impact is the main factor in producing the classic “reverse C” or “drawn bow” position (Figure 3, at right) that gets the whole body involved in the throw, not just shoulder and arm.

In that final transition of body weight from right foot to left block, there is no way to push or drive with the right leg and maintain the speed of the hips you generated in the run-up: If you sense weight or push off the right leg into the plant, you have lost much of the throw. It must happen faster than you can think about!

Quite a number of athletes have found some image or concept of “get off the left to get on the left,” or jumping across a puddle without concern of right leg drive, has helped gain consistently longer throws. As mentioned earlier, the right leg is very active in getting out of the way; the right knee turns in and down very quickly, so as not to support any weight, and allow the hips to move into the left block without loss of speed or any deviation from a flat path into the left.

Quite a number of athletes have found some image or concept of “get off the left to get on the left,” or jumping across a puddle without concern of right leg drive, has helped gain consistently longer throws. As mentioned earlier, the right leg is very active in getting out of the way; the right knee turns in and down very quickly, so as not to support any weight, and allow the hips to move into the left block without loss of speed or any deviation from a flat path into the left.

For example Tom Pukstys, former US record holder at over 285’ (Figure 4, at left), liked to think of sliding into the left side block. The action of the right leg upon landing from the last crossover is very soft (hence the “soft step” term) or quiet – almost a brushing of the ground without force or weight – with an immediate and fast pivoting on the right toe for that bent knee in/down action (or heel whipped out; same effect with a different trigger image) to put the body fully into the left block without loss of run up power.

This photo of WR holder Jan Zelezny shows how quickly he has rolled out the heel and rolled in the knee of his right leg before his plant has even landed; this is not a position that you can push from with the right (Figure 2 again). He’s running into his left side block in the same way a vaulter would run into the pole in order to clear a height: Strict horizontal force application against a resistance (box for vaulter, block side for thrower) that will give a vertical aspect without trying for it.

Notice I talk about a blocking left side, and not just the left leg. Here again, we look at the need to generate an elastic reflex action: there is a vertical one from the run into the block and a horizontal one from the reaction to a fully fixed left side. The rotation of the right side around/against the left block is hugely important to getting the high release speed desired. There has to be a firm base; from both the left leg and the left shoulder, to the throwing chest/shoulder/arm complex, has a base to stretch and re-act against. The concept or image of blocking sideways or closed, without your hips or chest facing the throw direction, is very helpful in mastering this important technical point. Look at that picture of Zelezny again to see his left side is pointed into the throw, not his hips or chest.

This is very much different from American ball-throwing sports that are where many javelin athletes come from. In football and baseball the throw is made from a fairly static position, so the left arm must move quickly and violently in order to put the throwing shoulder under stretch. That’s great when done in the NFL or MLB, but major injury time when done by javelin throwers. If the “soft step” right leg action is executed correctly the left side is jammed into the ground firmly and the right side – from the ground up – rotates around that fixed side like a door swinging on its hinges.

This is very much different from American ball-throwing sports that are where many javelin athletes come from. In football and baseball the throw is made from a fairly static position, so the left arm must move quickly and violently in order to put the throwing shoulder under stretch. That’s great when done in the NFL or MLB, but major injury time when done by javelin throwers. If the “soft step” right leg action is executed correctly the left side is jammed into the ground firmly and the right side – from the ground up – rotates around that fixed side like a door swinging on its hinges.

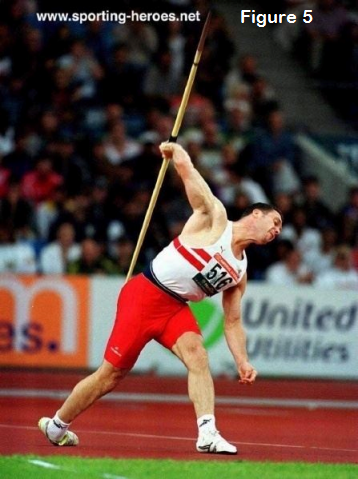

The hips, then chest will square up in the throw direction and stay there, putting a huge elastic stretch on the chest and shoulder that whip the arm and javelin out with great speed and power without willful effort or tension. A number of top throwers have related in some way the need to “keep” the left shoulder up or high; dropping the left shoulder during the delivery will cause a bending at the waist, a loss of both stability and elastic reflex and puts a great deal of stress on the throwing shoulder and elbow (Figure 5, at right).

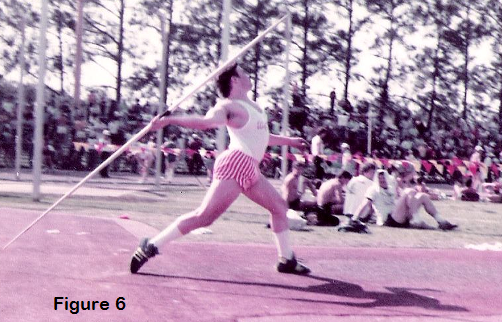

Imagine bench pressing on a waterbed – that’s what throwing with a dropped left shoulder is like. When done properly, the “soft step” with knee/heel rotation into the firmly blocked left side will generate big power and a lot of right side rotation around/against that left side “hinge.” Your big muscles generate power that gets into the javelin and your skeleton supports the body with little waste of muscular energy on trying to be stable (Figure 6, at left).

Imagine bench pressing on a waterbed – that’s what throwing with a dropped left shoulder is like. When done properly, the “soft step” with knee/heel rotation into the firmly blocked left side will generate big power and a lot of right side rotation around/against that left side “hinge.” Your big muscles generate power that gets into the javelin and your skeleton supports the body with little waste of muscular energy on trying to be stable (Figure 6, at left).

The importance of the left “hinge” side also is a factor of the use of the left arm in both the crossovers and into the block. In any effort to run faster, the action of the arms directly effects the turnover or speed of the legs – it’s why sprinters have such great upper body development. As a javelin thrower you have one arm rendered useless as it is involved with carrying the javelin. So you really need to work that free arm during the crossovers; it’s doing the work of two arms!

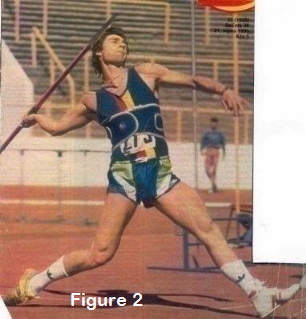

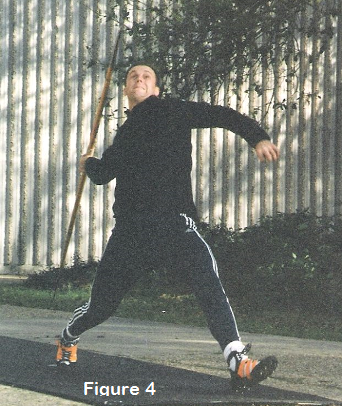

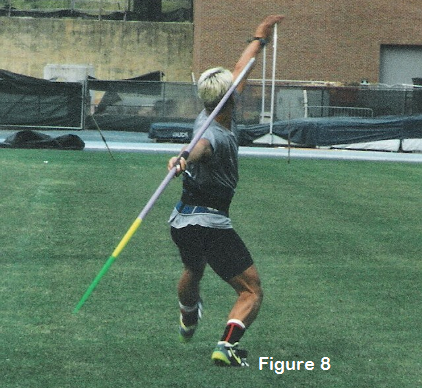

As you move in the crossovers to the block and delivery, you are moving sideways down the runway. Your left side is pointed into the throw direction, with hips and chest at right angles to the throw direction (Figure 7, at left). The action of the left arm should swing from well across the chest, as the right knee moves forward to pointing down the center of the sector, as the left leg recovers out in front of the body (Sequence 1, bottom of page). At no point during the crossovers and delivery should the left arm pull the left shoulder past a vertical line from the outside of the left foot (viewed from in front or from behind) (Figure 8, lower right). Remember, the chest opens to the throw because of the left arm swing into the throw direction is coupled with the rotation of the body against the left side “hinge,” and not from a baseball-style action.

As you move in the crossovers to the block and delivery, you are moving sideways down the runway. Your left side is pointed into the throw direction, with hips and chest at right angles to the throw direction (Figure 7, at left). The action of the left arm should swing from well across the chest, as the right knee moves forward to pointing down the center of the sector, as the left leg recovers out in front of the body (Sequence 1, bottom of page). At no point during the crossovers and delivery should the left arm pull the left shoulder past a vertical line from the outside of the left foot (viewed from in front or from behind) (Figure 8, lower right). Remember, the chest opens to the throw because of the left arm swing into the throw direction is coupled with the rotation of the body against the left side “hinge,” and not from a baseball-style action.

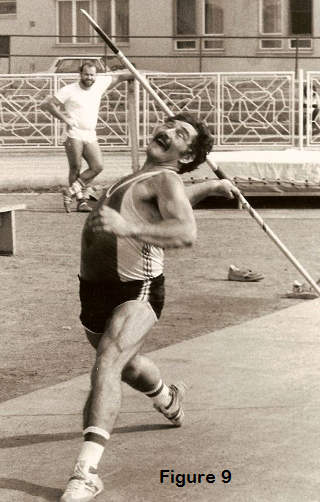

It’s immensely important that you work to have a very stable position when actually striking or slinging the javelin. Ideally, the chest is up, pointing into the throw direction and the javelin angle is perpendicular to the spine axis (Figure 9, lower left). If the chest keeps drifting forward, even if you have a wonderful chest “bow,” then your upper body is moving down – away from the throw – and you miss any point control or benefit from javelin aerodynamics (Figure 10, lower right).

The path of the throwing arm will most likely find its own correct and most powerful path if you have been correct in the crossovers, “soft step” and block. The old image of the arm and elbow passing close to the head or ear is quite bad; biomechanically, this angle is very weak and restricts you to the power of just the shoulder and arm. A fast, powerful  arm path is anchored against the left shoulder and will be more of a “3/4 arm” path (Figure 11, lower left) with a very long lever as compared to the “near the ear” arm strike. When done

arm path is anchored against the left shoulder and will be more of a “3/4 arm” path (Figure 11, lower left) with a very long lever as compared to the “near the ear” arm strike. When done  correctly the throwing action of the arm is fast, relaxed and a re-action to the rotation against the block side – there is very little you can do willfully at this point that won’t screw things up and cost you distance.

correctly the throwing action of the arm is fast, relaxed and a re-action to the rotation against the block side – there is very little you can do willfully at this point that won’t screw things up and cost you distance.

During the block and delivery is when your body is under the most elastic pressure, and having great mobility allows this big “bow” position to give you a very long pull on the javelin without undue tension. The throw just “happens” from the block/bow action, as long as the left side keeps firm. Pukstys commented on the javelin just “coughing” out from the accumulated power of run-up,  block and stretch. A whippy, fly-rod action of the arm is desired much more that a big, powerful arm throw. The arm transfers energy into the javelin, it’s not the source of this power. Think sling, not throw.

block and stretch. A whippy, fly-rod action of the arm is desired much more that a big, powerful arm throw. The arm transfers energy into the javelin, it’s not the source of this power. Think sling, not throw.

There are a lot of similarities between golf and javelin; rhythm and relaxation produce better distance that brute force. So I suggest the fall and winter training is very important for going to the driving range and hitting buckets of balls. You need to have a good volume of correct throws off 2-3 crossovers and from run-ups of various lengths. This is the time to correct mistakes and ingrain proper movements and make them second nature. While these throws are intense, it is intensity of quality and focus on being correct, not throwing hard or far. In fact, this is a good time to start to establish the relationship between correct throws feeling “easy” (many athletes relate that on their best throws it “felt so easy”) and you should see throws going farther  than the effort you put into it would make you think they would fly. If you do it right, it will go far; don’t try to throw far and hope it is right.

than the effort you put into it would make you think they would fly. If you do it right, it will go far; don’t try to throw far and hope it is right.

You can train quite hard in the weight room, throwing med balls and shots/weighted balls, bounding, jumping and sprinting – all of which will improve your physical abilities of speed and power. But never lose the connection between using your ability to perform correct technique; keep the correct feeling of the throw as you gain small amounts of new power. In this manner you can make modest gains in the gym, yet have all that gain find its way into the javelin. It’s more important to develop power for getting down the runway and stopping suddenly and completely; this is much more productive than making huge power gains and hoping some bit of that gets into your throw. That would be like driving a 12-cylinder sports car with five working spark plugs.

In conjunction with this you need to keep a positive focus, mentally. Develop the connection of positive re-enforcement in your training. Avoid negative feedback (“That sucked!”) and use positive input (“Get into the left side quicker”) as you go about your training and keeping your training log. Correct technical movements, soundly planned training and a positive outlook on how all this comes together will make for a difficult athlete to beat come the season!